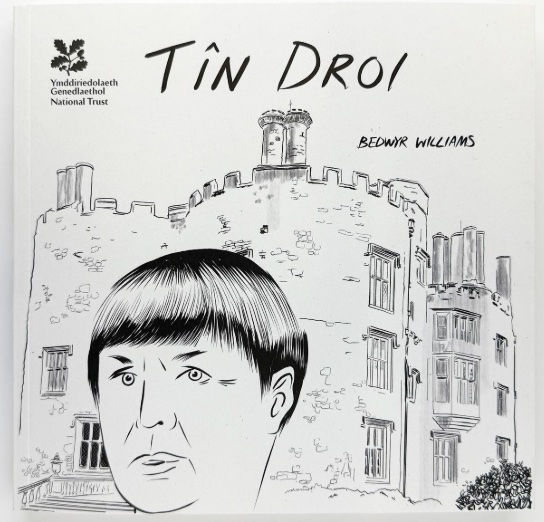

Can creative content be art? This question worried me as I picked up Tîn Droi by artist Bedwyr Williams. This book is published by the National Trust, commissioned by National Trust Cymru and promotes National Trust properties in Wales. So, I asked myself, whose beloved property is the end product?

The National Trust has had long association with artists, who generally emerge with their integrity in tact. Although conservative with a small ‘c’, they don’t make bombs or robotic soldiers: a good patron, then, much better in fact than, say, the Borgias.

But the Welsh artist is a prickly art world figure who, through longstanding use of a viral Instagram feed, has been using iPad drawings to satirise peers, along with the English, curators, second home owners, wearers of trendy footwear and, occasionally, writers. ‘No one is safe,’ observed an artist friend.

That IG feed is frequently hil.arious. In a style that is perfectly suited for the graphic novel he has now produced, Williams has developed a strong roster of characters and provides access to their inner lives. What they can smell, what they try to imagine, what makes them insecure but also too frequently what they hate. This contempt is absent from Tîn Droi. It would have to be.

The number of characters developed by Williams must number around two dozen by now. This book is a development of just two: a female airbnb cleaner and a male, plus size fashion victim. The longform was at first boring; no one to laugh at here/too much unpopulated scenery. But this unlikely collab, between a misanthropic bard and the marketing dept of a patriotic charity, ultimately works and goes deep.

Spending extended time with the cleaner as she judges and vapes softened me towards her. She is a curious, isolated woman, with a past of her own, searching for her place amidst these ruins. At the same time the ‘Man who absolutely loves clothes’, who has always made me chuckle into my phone, now has my sympathy. He too has enough love of life to get out and around to these historic properties.

And as if taking a break from showing masochistic cultural workers how the rest of the world sees them, via Instagram, Williams uses these 160 pages to show a heritage audience how two everyday people might see places of historic interest.

There are few dates, events, names or other historical facts. There are instead details you might at times overlook, from signage to cattle grids, tombstones to bench plaques, graffiti, electrical fittings, statues wrapped for winter, and of course the occasional antique. Perhaps by way of a nod to the origins of the project there are also plenty of smartphone interactions.

Rather than Can content be art? the question becomes Can art be content? On the evidence of this book, it is both content and discontent. In William’s intimate and honest audience survey — for a sample of two fictional characters — the customer satisfaction levels are ambiguous. That incalculability reflects well on both artist and client.

Tîn Droi is available for £14.99 here. Bedwyr Williams can be found on Instagram here. And there is a launch at Galeri Caernarfon on 5/12/25 at 6.30pm. The book’s protagonists might be there, in spirit at least.