Henri Breuil (1877-1961) has been called the father of prehistory. Little known in the UK, he should really take a place alongside Freud, Darwin and Marx as one of the scientists who sent shockwaves through 20th century thought; he changed the way we see our place in the world for good.

Breuil was a cleric, a scientist, and an artist. His copies of prehistoric parietal art gave the public its first glimpse of subterranean masterpieces aged between 20,000 and 40,000 years, He is reputed to have spent 800 days underground, at sites like Lascaux and Altamira. And he squared the facts of prehistoric life with his Catholic faith, just as he put his gifts as an artist or copyist at the service of his scientific mind.

Some work was done on the back of a proverbial fag packet. Having spent this week at the archive of the Muséum nationale d’Histoire naturelle, I come away with an uneasy sense that the first draft of prehistory was written on miscellaneous scraps of paper. Breuil threw away nothing and wrote, and drew, on whatever came to hand. But whereas his subjects reached for bone, antler, and rock face, Breuil was happy with recycled calendar pages and wine lists. From time to time, at least.

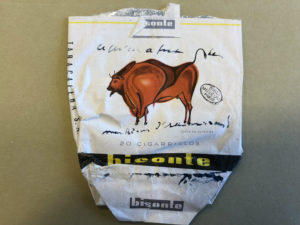

Breuil even writes on a literal fag packet (see picture): “Ce qu’on a fait de mon bison d’Altamira!â€. In some other words, Zut alors! Look what they’ve done to my Altamira bison! This iconic image, from the Sistine Chapel of prehistoric art in Northern Spain, echoes one of Breuil’s own copies. In his lifetime he published some 600 drawings, watercolours, pastels or oils. Plenty of material to inspire a graphic designer. It can be clearly seen that the newfound facts about man’s long history were marketable enough to sell a product with the clear potential to shorten your future.

Breuil was, by all accounts, a chain smoker. But it is hard to know what he felt about this instance of cultural theft. At least, the cigarette packet, as seen in box BR-7, demonstrates that knowledge percolates out of the academy by unexpected means. And that cave painting, a matter of national pride in Spain upon the discovery of Altamira, is no less likely a marketing hook than the 14m high roadside bull silhouettes which have, since 1957, advertised Sherry in Spain. But this love of the bovine goes way back.

If this has reminded you of any other marketable reproductions of cave art, please send them through to me at mark [at] criticsimsim [dot] com.

1 Comment

Hi Mark,

Just read your piece on L’Abbe Breuil and Bisonte cigarettes. It chimes with me in two ways: firstly, because I am trying to formulate a response to an example of cave art that was copied and used by an Australian artist James Cant as a logo for the Down Under Club in London’s Fulham Road in the early 1950s. Secondly, because when I visited Altamira in 1977, I bought a packet of Bisonte cigarettes. I’m sending you through an image of the cave art in question. In return would you be prepared to share your fag packet image? I will give you credit of course.

Best wishes, Simon