This is an artwork I heard about, and in truth there was nothing to see. Jon Carritt and Dan Palmer, two artists who share work space had erased themselves from an Open Studio weekend at Phoenix Art Space, Brighton. They had plastered over their studio door.

A few indications remained that there was once a work space here: a smoke alarm above the soon-dry plaster facade, names and a numbered indication on the weekend floorpan, or a recent memory which a visitor might have had that surely… there was a door here!?

I’ll quickly gloss over the pop cultural suggestions which hidden realms evoke. From The Secret Garden to Harry Potter, via Narnia and Doctor Who, any suggestion that an entrance is hidden is sure to set the imagination racing.

However, Carritt and Palmer are conceptual artists and having visited their studio I can report it is very minimal, with a few books, a dusty speaker, and a couple of tidy desks. If an art-loving Harry Potter fan had had the means (magical or otherwise) to break through this wall during Open Studios, they would have been sorely disappointed.

Phoenix studios on Grand Parade were replete with c.120 additional artists who were more or less happy to exhibit some of their output and welcome you to their domains. It was all part of a busy time in Brighton, in that merriest of monks: May.

This time of year ushers in our annual Open House season. Some 180 domestic venues across these environs offer you the chance to inspect other people’s kitchens, gardens and artwork. All this, as England’s biggest arts festival and its growing Fringe casts a jubilant shadow across town.

Carritt and Palmer had inevitably delivered a modest affirmation of the untrammelled spirit of play and creativity that can take over during a festival or a biennial. But it was also a negation of some aspects of this energetic celebration.

Brighton Open House Festival is, after all, a professionally organised event which allows 100s of local artists to monetise their practice, if only for a month now (and three weekends at Christmas).

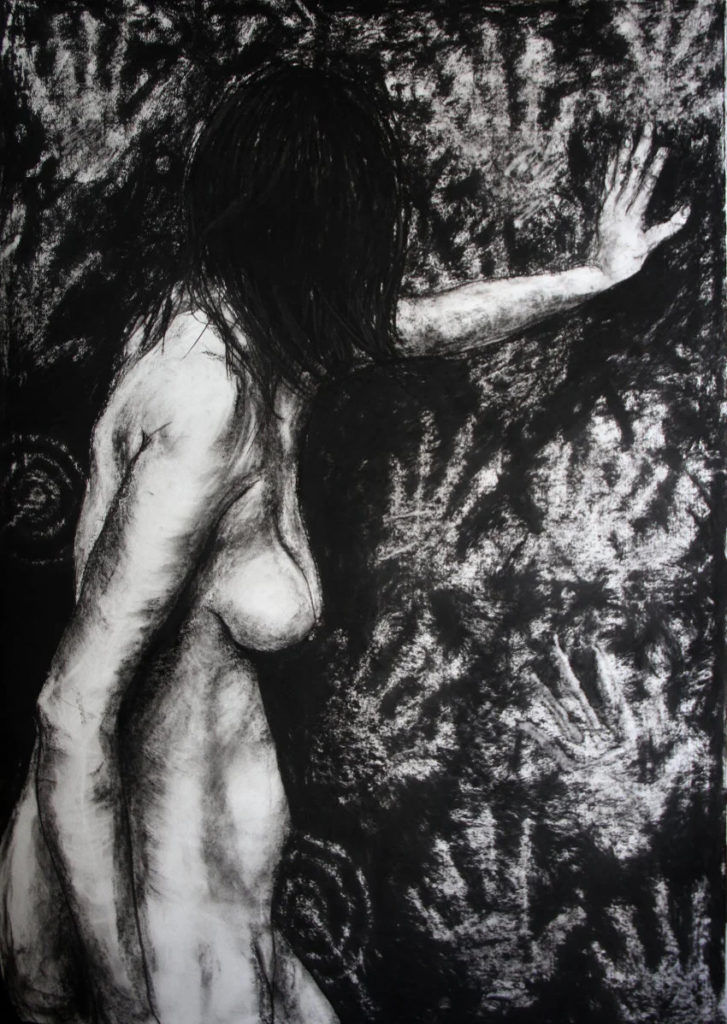

With a light touch and a hard edge, Carritt and Palmer build on their contributions from previous years: a plinth to block the entrance, video footage their studio on the locked door, a waiting ticket dispenser, a bouquet of flowers – with apologetic note. This year their studio was ‘colonised’ by Phoenix neighbour, painter Mike Stoakes.

I asked Carritt for a bit of explanation of all this, specifically I wanted to know whether last year’s building work had a title. He said: “If we considered it today as an artwork, we might refer to it as ‘disappearing studio’, or ‘plastered-over studio door’, but I’m not sure yet.”

That doubt, in a civic context where art and culture are promoted so aggressively, and blindly at times, is doubtless important. I wish I’d seen the artwork, if that it be, and I’m also glad, in a sense, that I didn’t.