Reviewing Thomas Hirschhorn’s Laboratoire des Monuments Tombés

That Thomas Hirschhorn should make an appearance in Caen was enough to provoke me to put family responsibilities aside and book a trip from Brighton, via Portsmouth. After six hours on the high seas, I was to arrive slightly dazed on Normandy shores, long after dark, armed with a code with which to find a room key, and lay my head down as a stranger in a strange land. The city of Caen was just far enough away that it might disorient, and the scale of the Swiss artist’s creation, was to confuse me even further.

I was reading a curious 18th century text, Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, better known as Gulliver’s Travels. And I was to find in Hirschhorn’s latest exhibition all it could take to magnify or shrink either the viewer or the reader. In six interlinked spaces I found trestle table islands in which small figures crowd around giant figures. The larger figures, though clearly devoid of life, are pinned down with cords in a way that echoes the opening part of of Swift’s strange novel. And as I gazed down at a crew of flat photographic onlookers, I felt that I too had arrived in Lilliput.

Gulliver’s Travels may feel a long way from #BLM or the Arab Spring, but it is a fable set against the backdrop of colonialism in an age of exploration by sea with at least one direct reference to the plantations of America. The eponymous narrator is a ship doctor rather than slave trader, but as he endures one shipwreck after another the shifting scale of the first two sets of natives that he encounters calls into question not only colonialism but also the rightness of governance at home: the six-inch-high Lilliputian emperor is absurd; the 40 foot king of Brobdingnag is too lordly for the business of state craft; there are reason-loving horses in charge, on the final island on which he washes up. They too find an echo here, in an equestrian statue that also falls from grace.

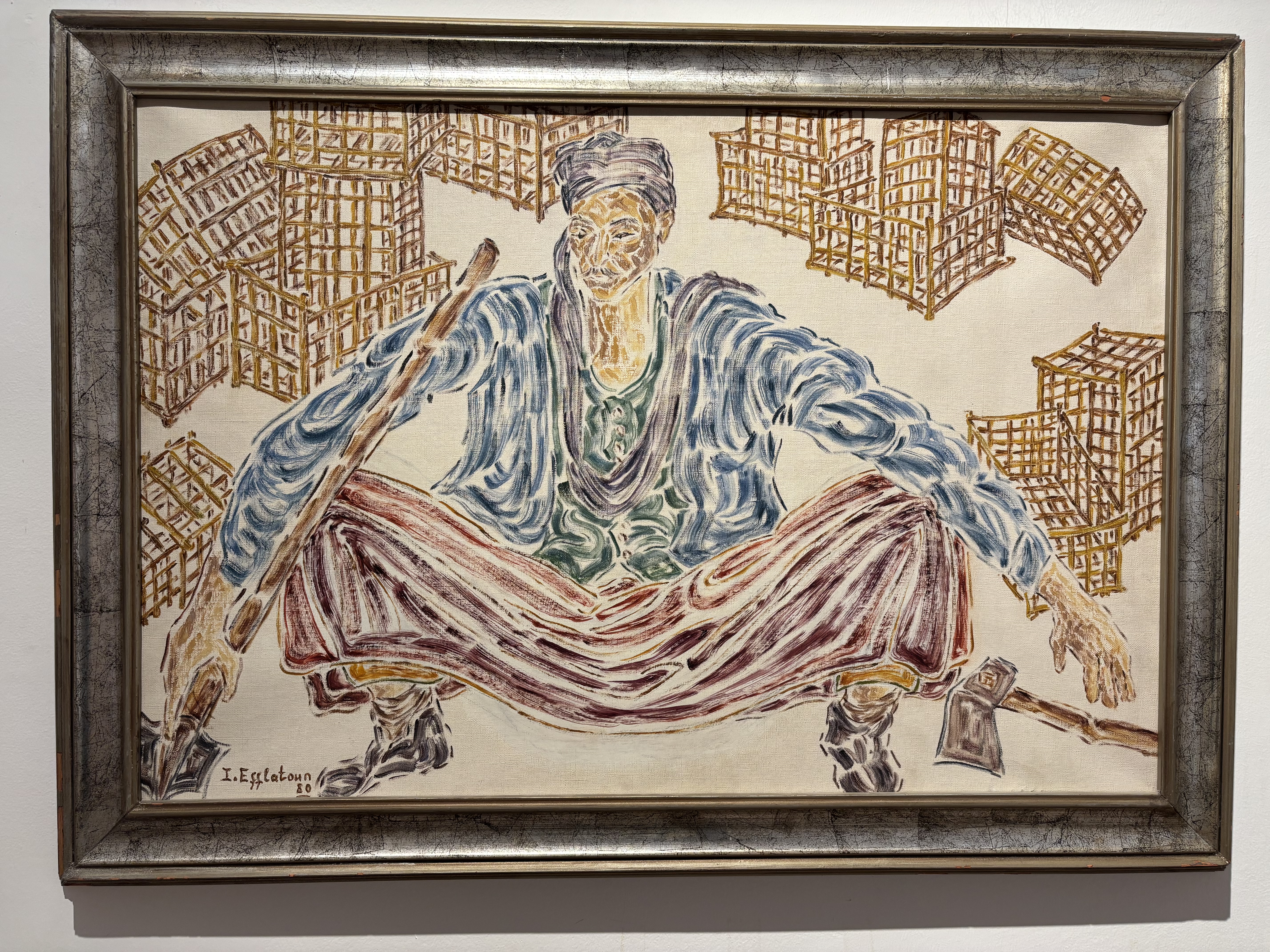

Like the wise equine Houyhnhnms with whom Gulliver would like to see out his days, Hirschhorn has progressive ideas; these emerges at times in written form. Previous installations have all featured a wealth of hand-scrawled maxims, slogans and quotes. For example, the Swiss artist has coined the maxim: “Energy, yes! Quality, no!” He based a show about vandalism and caves around the notion that “1 man = 1 man”. This exhibition in Caen does not break that mould. The artist is present, in the rough and ready sculptural construction, and the hundreds of placards which dot the landscapes he evokes or lie propped against plinth.

These placards, no longer needed, range from the violent (“By any means necessary”, “Murder”, and “Killer”) to the sweetly wholesome (“Keep it cool”, “Tell the truth”, and “Wake up”) One feels that what has been at stake, what the laboratory isolates here, is humanity’s conflict between hate and love. The conclusion to this experiment appears in block capital scrawl on one of the largest placards: “A MONUMENT IS A WORK OF ART IF IT IS BASED ON LOVE. IF IT IS BASED ON DOMINION IT IS NOT A WORK OF ART!”

It may seem perverse for a sculptor to present a show in which most of his plinths are starkly empty. The crowning bronzes, sketched out here in dark packing tape around crude cardboard frames, are all toppled, which is no surprise given the French title, as Hirschhorn has chosen the ongoing strike against statues for the premise of this aptly named ‘laboratory’ in Caen. There is a clinical dimension provided by the translucent plastic sheeting that encloses the visitor at all times and the plastic drapes, not unlike those which keep the temperature low in a cold store, must be pushed aside to move from one political spectacle to another.

These Lilliputians are generic human forms, images found presumably online, printed and stood tall with the help of two-ply cardboard. Gigantic Gullivers are also here, by proxy, toppling off plinths as less desirable human types: the general, the dictator, the plantation owner or the confederate. Rope and cord heave at these mighty individuals and the viewer comes across the scene at the moment when, under lab conditions, the monument has fallen.

I felt a little like a Brobdingnagian myself. I was also a giant who, secure in my size and strength, enjoyed some detachment from these scenes of human turmoil. This laboratory is at once stirring – you could get caught up in this mass movement – yet also didactic with a clarity that brings you calm.

The felling of statues has been identified, as a movement which began in Algeria in 1962 – I knew this from Nicholas Mirzoeff’s important book on white supremacy and visual culture, White Sight: Visual Politics and Practices of Whiteness. From the North of Africa it spreads South, culminating in 2015 in post-Apartheid South Africa. In even more recent years attacks on monumental figures has reached the shores of Britain and the US. Yet we shall always have a long way to go. Mirzoeff informs his reader there are no less than 700 confederate statues on public land. It’s gonna take a lot of spray paint and rope. It’s also going to take plenty of courage. New legislation offers more protection to statues than you might expect for women, or the trans community.

Mirzoeff finds a global network of statues so common as to be almost invisible. They construct an infrastructure of white supremacy. They seem to watch us, from on high. (And have not a new network of patriarchal and racist state actors, and tech oligarchs already placed us all under surveillance?) There is some obscurity, even anonymity, to certain historical figures which UK and US city planners opt for (Hirschhorn asks at one point with great pertinence, who to honour, “Qui honorer?”) And yet in some cases these impervious, immortal bronze goodly types have witnessed lynchings and ralllies, by the Klu Klux Klan for example, at their feet. Attacks on the statues themselves are more resonant than might be expected. With so much going on, it is little wonder that Hirschhorn wants to get all this evidence back to the lab.

There was, however, nothing clinical about the 2014 success of the Rhodes Must Fall (RMF) movement. The downfall of this apartheid figure in supposed post-apartheid South Africa was messy. Protestors were to fling human shit at a controversial statue of Imperial governor Cecil John Rhodes, because access to sanitation is a live issue in S.A. Scenes closer to home from the BLM demo in Bristol, in which Edward Colston’s statue was to be torn down and cast into the sea, were also riotous. Hirschhorn, a very rational artist, finds these scenes rife for investigation.

What he finds here and what he distils is rage. An RMF academic and activist Leigh-Ann Naidoo is quoted by Mirzoeff as saying: “The conduit of rage is awareness of another possible world in which that violence does not exist”. From anger to Utopia then, ours is a journey from captivity to freedom with parallels to that of Gulliver. Hirschhorn’s gallery of 2D spectators surround these scenes of desecration, and look on in static contemplation. They are a generic bunch, these some hundred onlookers, dressed for tourism or for hiking, not one keffiyeh or balaclava between them. The pint sized onlookers stand with us, to face the dawn of a new post statue world.

This exhibition is an effective way of harnessing the insurrectionary power of ideas and collective action. The artist’s ambition has led to some notable staging posts on this redemptive journey. He may be a sculptor with a feel for the monumental, but his previous monuments – dedicated to the likes of Gramsci, Deleuze, Spinoza and Bataille – have all been gestures of ephemerality. Knocked up quick with plywood, packing tape, plastic sheeting and armies of interested locals, they emerge for a period and then disperse leaving a glimpse of a better world.

No one could deny that these temporary monuments, very often habitable, sometimes puzzling, always curious, have been made with love. It is equally clear that civic orders to install hundreds and hundreds of weighty portrayals of colonial figures across the Global North have nothing to do with art. Any violence needed to tear down a civic monument has the rough and ready energy that Hirschhorn seeks in all his work. What comes next is up to us? Not all the lab results are back yet.

I slipped through the final set of clear plastic drapes and wandered back through the gallery. The streets of Caen looked undisturbed by the staging of these six miniature uprisings. But I think I’m now contaminated by hazardous lab material, or overseas ideas, like those met by Gulliver; I find myself anticipating more monuments tombés. I will look out for them everywhere now.

Laboratoire des Monuments Tombés is at L’Artothèque, Caen, until 7 June 2025.