Goiing underground in Maharashtra

I took a boat from India Gate to Elephanta Island, exchanging the dense throng of cars and bikes for a vast company of lively ferry passengers sweating in the Chirstmas-time sun. Our boat left the mainland and we chugged along for a full hour before reaching a quay on Mumbai’s neighbouring rock, where a young guide attached himself to me with a persistent level of ingratiating chat about cricket. I knew nothing about cricket, but he was not perturbed. He was as persistent as various hawkers who lined the steps from ferry dock to a fifth century rock-cut cave complex, which gave its name to the island.

The portico for this warren appeared sunk into a green hillside. The seven columns were as squat as legs from two giant pachyderms. They shared a dusty yellow hue with the rocky hillock behind them. These legs were the first glimpse of an achievement by the workers who more than 1500 years ago, in their hundreds surely, chiseled a deep, cavernous structure out of solid rock. The dark spaces hinted at what might lie inside.

I was left very little time to speculate as my guide marched me through the nearest recess and toured me around the depths of the 39m long cave, stopping only briefly to take in a towering statue of Shiva which showed the goddess in all her forms as the Creator, the Preserver and the Destroyer; each of Shiva’s faces had two names and, oh, here were seven more gods whose names stretched to a total of 43 syllables.

It was 2018 and I was in the earlier stages of a PhD about the representation of prehistoric caves. And, like the good academic she is, Prof D took this venture very seriously and arranged for me to see two more such caves in Maharashtra. Much like the Elephanta cave complex, the state’s two-part attraction, Ellora and Ajanta caves, do not date back to before any known civilisation. In this way, they differ from the prehistoric painted caves of France and Spain. Yet all three UNESCO sites are still staggering, and staggeringly ancient: at once crowded, and yet well off the beaten track, for me at least, when compared with the Dordogne.

Visits to these Indian caves are not regulated in the same way as their palaeolithic counterparts in Europe. Tourists are free to roam, and, at Ellora, Prof D and I were to thread our way around what must be one of the world’s largest, and perhaps only, immersive sculptures made out of basalt. To be in the largest space, Kailash Temple, felt like being at the bottom of a quarry, surrounded by a phalanx of stone elephants. Beyond these, the cast of sombre gods, whose figures we passed below and between, looked on in sublime indifference to our wonder.

In my mind’s eye, Ellora is two realms. In the open air it is baking and parched, a scrub with paths worn around the complex between the opening to cave after cave. These number more than 100, which gives the site an epic scale not totally unlike a theme park or a zoo. The carvings pertain to three major Indian religions, Jainism and Buddhism as well as Hinduism. If you time it right, you can ride a minibus to the further reaches. Beyond this setting of dry trees, dust and rock, are the dark, cool hollowed out spaces in which the casual tourist can never know what to expect.

But then again, how might a casual tourist even reach a tourist sight like this. The next day our casual status was tested by a three-hour, axle-punishing drive to Ajanta. Dating to the second century BCE, this complex is older than Ellora and Elephanta. It is solely Buddhist. At one time, the 30 grottoes there comprised a highly decorated monastery. And yet by casual accident, a nineteenth century Britisher ‘discovered’ the cave: a cavalry officer with the forgettable name John Smith.

Although the site was well known to locals, in 1819, J.S. stumbled across Ajanta in the course of a tiger hunt and proceeded to carve his boring name, in full, across the painting of a serene bodhisattva, who, like the local tigers, had never done him any harm. ‘He’s a total asshole!’, you might be thinking, and you might have a point. But, by this simple act of vandalism, he seems to prove that imperialism has a philosophy and practice as developed and rewarding to its adherents as the teachings of Buddha.

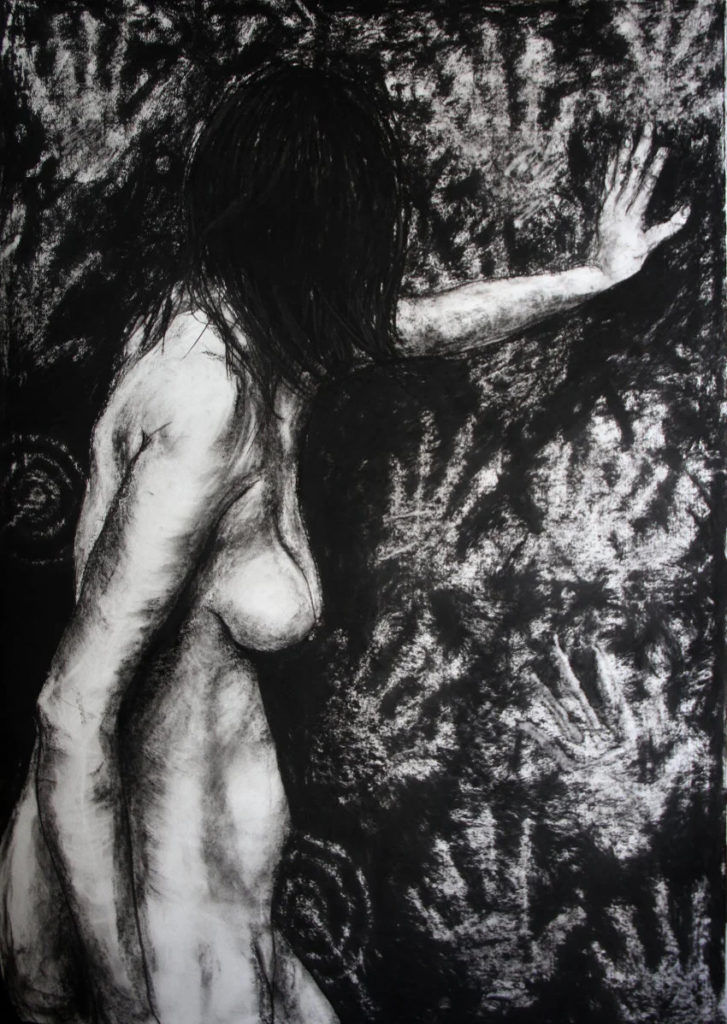

Ajanta is a string of monastic cells, forming an ambulatory sequence along an uneven path around a cliff face. It has more subtle charms than the gigantically carved caves we had seen so far. It has paintings and engravings pertaining to sutras, godheads, and divine plans. One inspects the ruins of these images in the glow cast by low level lighting, or the torch on a phone. The parietal works at Ajanta repay the time spent in queues and, even given the crowds, can still evoke the Buddhist calm, and thus retain some of their holy purpose.

I’m afraid Prof D and I find ourselves on a path of devout agnosticism. Whether in India or in Europe we embrace the chance to enter temples, churches and shrines. At Ajanta we embraced three dozen such spaces. Visitors are free to work their way along one side of a valley surrounding the River Waghur and to hunt in the semi-darkness for icons and expressions of longstanding faith.

We may be among the last to do so. Construction is underway on a suite of replica caves, attached to the visitor centre here at Ajanta. If you’re at all able to visit for yourself, you have two options: 1) be quick before they find the necessary funds to replicate the experience and close a number of caves to the public, or 2) enjoy the replica, as I was able to do at Lascaux, and receive a vivid picture of the works which, ironically, will offer you the best possible view.

Via replica, you may reach Satori, and you will see Ajanta in a way that a buddhist in the second century BCE could only dream of! Indeed it joins the global ranks of heritage sites which have doubled and, even, via second-hand reports like this, tripled.

Trip was in December 2018. Image is from Ajanta Caves.