An artist and I stand on the summit of Whitehawk Hill, atop the hidden remains of a neolithic encampment. He is dressed in black, and smokes actual cigarettes, as I might have expected. Beyond that I’ve little idea how this meeting, with one of Folklore Twitter’s dark luminaries is about to play out.

The setting, a prehistoric site we both chose, is disappointingly nondescript. I had hoped it will channel some chthonic energy into the piece you are about to read. But for the time being, myself, and this leading online goth and Brighton-based artist, contemplate a mobile phone mast. He seems to love it!

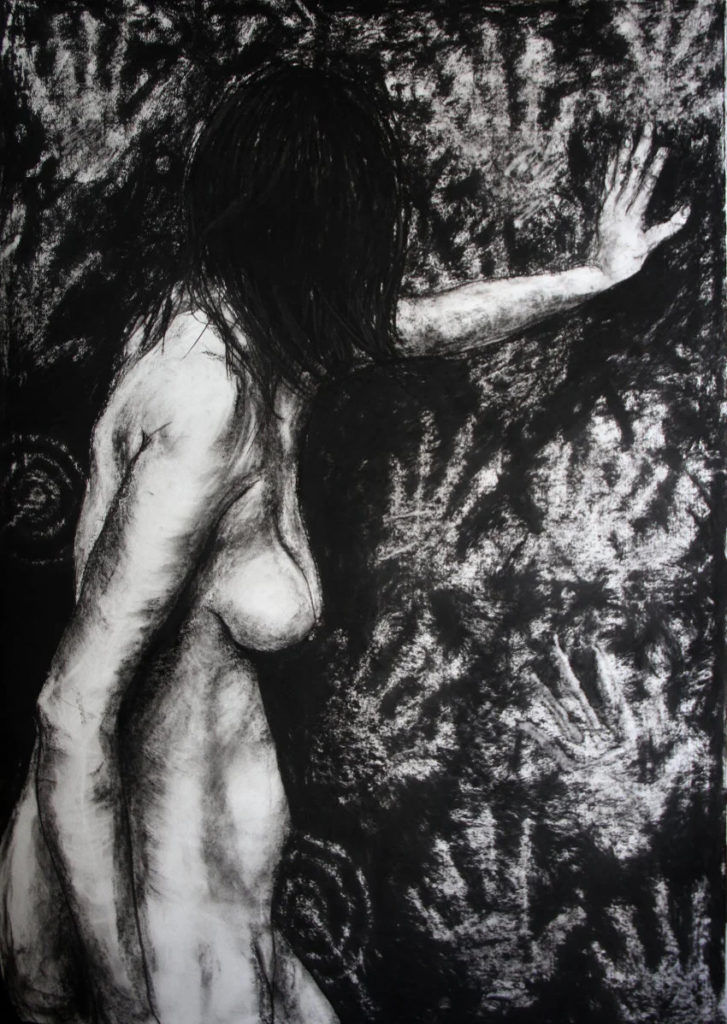

“I don’t believe in magic” he tells me later in the East Brighton cafe to which we repair. But, dimly, I had thought of Paul Watson as a serious occultist, with a suitably esoteric vision. His last published body of work comprises of shadowy charcoal figure drawings of gloomy naked models. These subjects looks so close to the relic-littered soil of old Albion. His drawings reference myth, pagan spirits, and a spirit of utter dejection which is very 2024. (Watson has an abiding interest in the English civil war).

To further characterise his drawing, I would say that his figures are very inward. In charcoal, their bodies are pale or grimy, never warm or especially inviting. Whereas classical life drawing conveys a sense of anatomical fidelity, Watson seems to dispense with flesh in favour of bone. His men are stony or grave rather than vigorous; his women perhaps dented rather than curvaceous.

Their environment can change; it is a background of midnight black in that series, a featureless sepia desert in the latest. Sanguine pencils, rather than charcoal, give his figures renaissance pedigree, quite at odds with the mood of fin de siècle Viennese expressionism. His photography, in which he shifts gears again, is stark and notable for the models’ otherworldly masks; and Watson makes these himself.

Masks lend his sitters an air of atavistic power. It will amaze you, for instance, how a muzzle of ivy or an eye mask of oak leaves can imbue a stranger with great mystery and potency. You wouldn’t want to meet many of these photographic subjects on a dark night, and yet in their world it is always night.

There is a vital intrigue here, because in person Watson is approachable, open and upbeat. For all the obscurity of the pagan rituals he seems to evoke, he offers complete transparency of means. He makes books, because these are more accessible (“People are in this country are far more comfortable buying books, than buying artwork. They know what to do with books.”).

He also runs a detailed commentary on his practice at lazaruscorporation.co.uk. He is upfront about his paper, his pencils, and his process. If he is searching for a life model, you will read about it. Even his thoughts about blogging are right there, on the blog. He will also, endearingly, wear his musical influences on his artistic sleeve, having stayed true to a few bands from the 80s which I, for one, have been trying to forget. Perhaps unfairly.

On the one hand he still inhabits an eldritch isle. His book England’s Dark Dreaming assumes the guise of a semi-mystical pamphlet. Watson took inspiration from ‘samizdat’ publications dating to the English civil war. “I started that after the Brexit vote,” he tells me, “and it was very much a cry of rage at the growing right wing presence in England”. Watson quotes the words of ‘landscape punk’ David Southwell, who claims that ‘reenchantment is resistance’. Watson concurs, aiming “not to view the world purely in materialistic terms and to use whatever is available to find wonder in the world.” Such wonder, he seems to say, will always elude the price tags of late capitalism.

On the other hand, he is unafraid of the light of day. “I don’t see any paradox,” he says, “between an enchanted world and a demystified process.” Watson might be horrified were I to present him as angst-ridden as, say, Ian Curtis. “I’m not interested in building on that whole artist myth of tortured genius,” he says. “I like demystifying the whole thing. I don’t think it takes away from the finished piece. I think it adds to it this whole thing.”

How else, in the age of deep fakery, can you be verifiably real? Of his masks, for example, he says: “It was definitely not AI. It was crafted with glue and petals and wood – whatever I was using.”

And here is the total artistic programme. When Watson is not coding software in his day job, he is working, as if from command-lines, series by series, on an attempt to create a vehicle or a lens to allow us all to imagine the unimaginable: namely the end of capitalism. Watson’s latest works are influenced by an unpublished, unfinished work of the late Mark Fisher, the theorist who is best known for saying the end of the world is easier to imagine than a working ideological alternative to the current Neo-liberal worldview.

Watson picks up: “I think that is true. It is very difficult to imagine something different from capitalism, so what I’ve been trying to do with Acid Renaissance [the most recent series – see above – which in fairness is warmer and lighter] is to break the imaginative chains by going into the mythic again and then start to imagine this future England almost like a social anarchist state”.

In these sepia scenes of Leonardoesque cartoon we are confronted by details that Watson must hope we can take forward into that unimaginable future; here a laptop, there a wheelchair, in one, even and especially, wind turbines. Despite some deep historical references, Watson is clear he would like to effect change in the present. “I’m not interested in going back to the past, “ he says. “I’m interested in going to a post-industrial future”. Yet it is no pastoral idyll which the artist has in mind. “I’m fairly healthy but there are many people who rely on electricity and having the infrastructure of hospitals and things like that. So I very much don’t like these back-to-the-land fantasies. I think they’re fascist, because you’re essentially saying: we can kill off this part of the population. So I think you’ve got to imagine this post-industrial future which still does have things like electricity and healthcare”.

If that sounds difficult to imagine, perhaps it will indeed take a truly widespread, far reaching renaissance of an acid nature for us to collectively hallucinate what Mark Fisher’s idea of impossibility might actually look like on this planet of ours. In the meantime, we have Watson’s coming book.

Whatever the future, there is something which the artist believes is essential to human expression. “I think there’s something very fundamental about creating images of the human body,” he says. He compels my attention with an image in England Dark Dreaming in which one of his mythic, future-past characters is making handprints on a cave wall. In this common palaeolithic act the body is implicated in “the very earliest form of art.”

Having spent six yeas of a research degree trying to put the term ‘cave art’ into question, I am not sure. But whatever the case it was grand to stand alongside such a thoughtful and committed contemporary artist on the site of an encampment dating back 5,500 years and look across our city by the sea.

As Spring sunlight played on the water and the South Downs offered Brighton’s denizens their protection, we imagined being able to look across to the summit of Chanctonbury Ring by night and to see a bonfire. This mental journey back in time felt easy in the present company. Or was it a journey into the future? Reaching for my smartphone I took my own photo of the phone mast and we hiked back down the hillside.

For more information on this artist, and to read his generous writings and/or view prints and books for purchase, visit Lazarus Corporation.

No Comments