For those who don’t already know, Aston Villa FC are an underperforming English football team from the West Midlands. It might not be common knowledge in the wider art world.

Three artists staged a gallery event last Saturday: Bartlett, Selmes and Roberts. We’ll drop the first names, in the spirit of football. Because all support ‘the Villa’.

And all three wore the team’s claret and blue shirts and in doing so took on a radical (or alarming) non-art look. They didn’t even look like performance artists. It was perhaps anti-anti art.

The terrace vibe was helped along by an atmospheric loop of crowd noise: grown men professing their loyalty to this historic club and its players through the medium of chant.

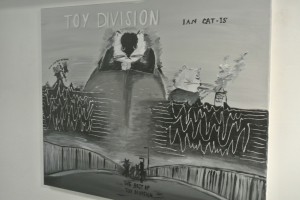

Meanwhile, the ‘art’ was a collection of doctored pages ripped from matchday programmes and merchandise catalogues. A 90-minute projection showed AVFC demolish Birmingham City 5-1.

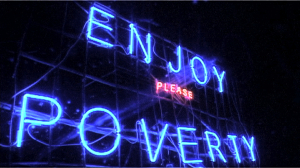

All of the above was fiendishly parochial. Players who had been gods in their time, were reduced to the status of an in joke. Was this about the idiocy of football or the selective ignorance of art?

There were also beers. There always are at openings. But these were an assortment of different brews, with each one themed around a first team star. This blogger opted for a Darren Bent lager.

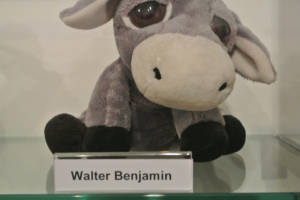

Another attraction was the Lambert Out campaign, by which Bartlett attempted to drum out the club’s under fire manager by handing samizdat posters to bemused gallery folk.

If you like football, the whole thing was a total hoot. But what many overlook, and which you could have learned at this show, is that the most interesting things happen off the pitch.

What to make of the current prime minister David Cameron and heir to the throne Prince William? Both claim to be lifelong Villa fans, to Bartlett’s horror. It’s a surreal carnival.

Art’s perspective on football may be as narrow as football’s perspective on art, but both worlds could surely learn from one another. You will, for example, find art at football grounds.

Portman Road is the stadium for my team de choix; on a plinth outside is a statue of former manager Bobby Robson. It is made by Ipswich fan and sculptor Sean Hedges-Quinn.

Home fans arrange to meet by this artwork. They pose for photos here, and roundly approve of this tribute to a local legend. One presumes they even admire the likeness. No soul searching here.

Just be warned. Football art cuts both ways. This blogger once got a text from a friend who saw fans from another club urinating on the likeness of our hero; Robson died of cancer five years ago.

That’s a pretty direct critique, which this blogger could only dream of emulating. Art people might still piss all over your latest show, only with the ambivalent gift of metaphor.

Work Programme 71 took place on Saturday November 15 2014 at Community Arts Centre, Brighton. See gallery Facebook page for future events.