Not everything that gets hung on a wall purports to be art. Certificates, contracts, constitutions; all these have at one time or another been framed and put on display.

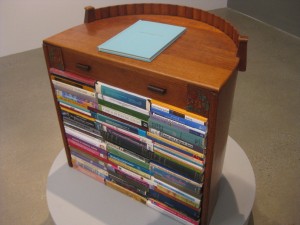

Counter Offer is hardly an aesthetic statement. It comes across as a legalistic exhibit, a founding document of the type which reminds you how much weight words on paper can carry.

Carey Young presents an offer of freedom followed by an offer of justice, with the proviso that the first offer will be “automatically withdrawn†upon the making of a second.

This suggests more than 100 years of political history boiled down to a bloodless struggle between two pieces of paper. You have the freedom to spend money, but not if you agitate for equality.

You might wonder why freedom is offered on the left and justice on the right. But then freedom could also be emancipation. Justice may take the form of fascism.

The four ideals cannot co-exist. That paradox exists not merely as a sad fact of human life, but as a matter of law. And the legal framework accounts for all our freedoms and servings of justice.

As for what underpins this framework, who knows? Just maybe, it is art, because this piece puts our rights and wrongs in the balance. And now we are stuck with justice, whatever that means to you.

You can read an earlier post about Carey Young here, or go to Culture24 to read my review of her show at Cornerhouse, Manchester.

Counter Offer can be seen there in the exhibition Memento Park until March 20 2011. See gallery website for more details.