Putting out the flags has become the most recognised gesture of welcome in every part of the world. Here we all are, they say, together in our differing categories.

Seen all at once, they inspire optimism. All these national emblems will fit on the end of a flagpole or a world cup wallchart, so it stands to reason the countries themselves may co-exist.

Indeed the 36 raised pennants on the outside of the Scandinavian Hotel flutter in the same breeze. On a sunny day, they look more or less the same.

But the cosmopolitan mood soon darkens. The flags in Flame Test appear to be burning. On closer inspection you realise that each of these nations is guilty, and their guilt makes them distinct.

Having been printed up from actual press agency photos, the installation brings home how much each of these countries is somewhere hated. It is hard to continue subscribing to the innocence of flags.

Perhaps we would be better off without our categories, certainly we would be less likely to go to war. Burning one flag is an act of hate. Burning them all is surely an act of love.

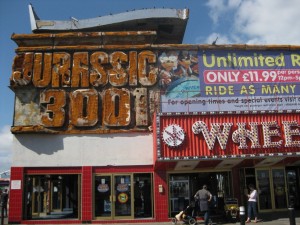

Flame Test can be seen at the former Scandinavian Hotel, Liverpool, until November 28 2010, as part of the Liverpool Biennial. For more details visit www.biennial.com.