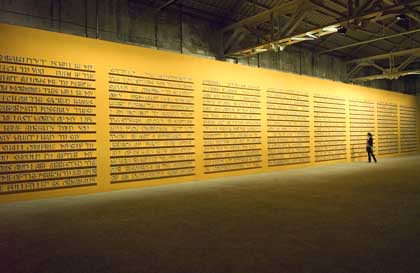

The very first gallery pays homage to Ghandi. 4,479 fibreglass bones spell out a text which pleads for non-violence so it seems perverse to name this show The Empire Strikes Back.

But violent reactions wait round every corner of the Saatchi Gallery’s 11 main spaces. On this evidence, Indian art causes shudders, sharp intakes of breath and widening of the eyes.

The worst of the horror comes from Huma Bhabha, who has created a praying figure wrapped in a bin bag. Ancient clay hands extrude, as does an antediluvian tail. It looks like a rodent or execution victim.

The most gasp-inducing work is by Jaishri Abichandani, titled Allah O Akbar (which translates as “God is great”.) It’s written in glittering red and green whips, conveying both the rigors of Islam and the dubious glories of martyrdom.

Then there is the awe-inspiring presence of Eruda by Jitish Kallat. This dark sculpture of a Mumbai street child stands more than 4m high. He carries books for sale, heroic in a Disneyesque way. But touch him and the black-lead finish will stain you.

The shock factor is what you might expect from this gallery and at worst it can seem one dimensional.

Arabian Delight by Huma Mulji is a taxidermy camel in a suitcase. It’s undeniably funny but, as a comment on the Islamification of Pakistan, it is fairly closed off to interpretation.

But at best, such high impact work can astound and violently re-orientate you. A piece called The Enlightening Army of the Empire might suggest a choleric phalanx of men in red tunics with muskets.

Instead, Tushar Joag presents us with a skeletal, spectral band of robotic figures, who wield car lights, spotlights, neon strips and lightbulbs.

It strikes you that the British must often seem strange to India. Indeed, it is strange and enlightened that this exhibition should take place at all.

Three floors of Indian art have been made available for free, together with a picture by picture guide – one of the best you are likely to come across.

So come and let the works do violence to you. They should be resisted passively, if at all.

Written for Culture24.