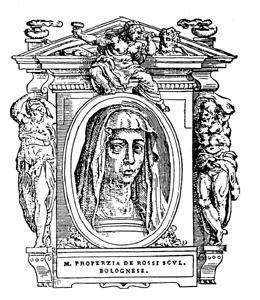

Of the 35 renaissance artists to feature in this copy of Giorgio Vasari’s The Lives of the Artists, there is only one woman. And it is a surprise half way through Book III to discover even one.

This was Properzia de’ Rossi and the three pages dedicated to her life are among the most engaging in Vasari’s exhaustive and occasionally riveting masterpiece.

It may be apocryphal, but she is said to have proved her fine art chops by carving a multitude of figures into a peach stone for a scene of the passion of Christ.

But her greatest triumph was to carve a marble panel, which, Vasari claims, reflected some of her own autobiographical circumstances, on the doors of San Petronio in Bologna

The scene in question comes from the Old Testament and shows the wife of Potiphar disrobing for Joseph in a bid for his attention, ‘with a womanly grace that is more than admirable’.

De’ Rossi was also suffering from unrequited love and a footnote in the Oxford World’s Classics edition reprimands Vasari for ascribing mere ‘romantic or sentimental inspiration’ to a woman.

But seems to me rather that this work is all the stronger for the apparent comment on de’ Rossi’s own life. It gives the work so much more honesty and front.

And if women were generally excluded from public life in 16th century Bologna, what Vasari calls this artist’s ‘burning passion’ may have been socially challenging. It’s almost Tracey Emin.

Or am I just lumping women artists together? in the same way Vasari does when he uses his chapter on de’Rossi to fill us in about Sister Plautilla, Madonna Lucrezia and Sophonisba of Cremona.

He tells us that in one drawing by the latter, ‘a young girl is laughing and a small boy crying because, after she had placed a basket full of lobsters in front of him, one of them bit his finger’.

That does seem very early in the history of art for comic lobsters, only perhaps not so early for proto-feminist statements.

No Comments